Authored by: Manasa Visakai, Content Producer

Expert Input: Sebastian Harvey, leading facilitator and coach

A contact officer does not organise interventions or provide direction on workplace issues. Instead, they need to act much more as a sounding board.

For several years now, a contact officer has had an integral role to play in facilitating level-headed conversations with vulnerable employees and maintaining impartiality and confidentiality, while determining whether a workplace issue requires escalation or not. This responsibility sets contact officers apart from a regular HR member or direct supervisors.

The Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) defines contact officers as ‘a harassment officer, equal opportunity officer or equity contact officer who is a staff member that assists employees who experience discrimination and harassment in the workplace’.

Despite being such a nuanced role, there is a general lack of awareness across organisations as to what a contact officer does and more importantly a broader commentary around their necessity and relevance.

In order to help organisations, we interviewed Sebastian to shed some light on the key responsibilities of a contact officer and how their role differs from an HR or manager when having conversations around unfair treatment.

Workplace Contact Officer — Why does your organisation need one?

When an employee walks in with a workplace harassment, bullying or discrimination complaint, a contact officer needs to strike an initial conversation that focuses on making sense of what’s going around that workplace behaviour and clearly outline the alternate options that the employee can pursue.

For organisations questioning the need for having contact officers, it is important to shift the perspective to understand what value they bring to your people. With active contact officers in a workplace, people can gain the confidence to talk freely about workplace issues, and therefore, move the needle on the prevention and management of serious issues like sexual harassment and bullying.

“Organisations today are required to prevent and manage allegations of harassment and bullying, and since it’s been written into the sexual harassment legislation, there’s a much greater focus on prevention,” says Sebastian.

Harvey suggests officers approach an employee’s workplace issue by thinking about ‘bringing an issue to the manager’s or HR’s attention, getting external specialists involved or by looking at other psychological support that might be appropriate’. Having trained multiple employees to step into the role of a contact officer, as part of iHR Australia over the years, Harvey explains that “Once a decision has been made by an employee, the contact officer can very much step back and let things unfold.”

“Whereas if a manager or HR were having a very similar, initial conversation, it is most likely going to turn into a workplace intervention,” he adds.

In a case where a harassment or bullying claim turns into an adverse action or unfair dismissal, the court tends to look at the evidence. If the organisation has an existing contact officer who had acted as one of those pillars an employee could rely on, it can imply to the court that the organisation has treated the claims in a serious manner.

If employees have access to the contact officer’s network, the court may use this when considering where the liability lies — is it a direct liability with the individuals who have been accused, or an accessory liability in relation to a manager’s incompetency or does the organisation carry a vicarious liability due to the organisation’s gaps in preventing harassment and bullying from occurring.

Do the recent updates to the Sex Discrimination Act have an impact on the duties of a Contact Officer?

According to Sebastian, it essentially does not change or add anything significant to a Contact Officer’s role. However, the changes to the Sex Discrimination Act does put the onus on an organisation’s managers and leaders to be more proactive in prevention. This might include updating bullying and harassment policies, being observational about the workplace culture, and tapping a reliable and resilient employee to take on the role of a Contact Officer to focus on early prevention.

Making early prevention a priority is indicative that the organisation has an employee who is not necessarily acting with authority but has been assigned the power to initiate conversations to prevent things from escalating.

How do you find contact officers within your organisation?

Contact officers are often not hired but are selected from within the organisation.

For this reason, Harvey suggests organisations focus on identifying trustworthy employees for the role of a contact officer: One who is credible, can build rapport and maintain confidentiality with other employees. The process can involve identifying key people, tapping them on the shoulder and asking them to be contact officers, or “having an open selection process where people can nominate and go through a whole selection process,” he adds.

Furthermore, organisations need to realise that an existing employee who takes on the role of a contact officer is only carrying out an added responsibility, which is separate to their normal job role.

When exploring potential employees who can act as good contact officers, Harvey sheds light on how nominating an organisation’s HR people may play out as a setback.

“While it’s good to train your HR people to understand what contact officers do, it’s necessary to have a cohort of contact officers who sit outside of HR, and also part of that cohort excludes managers,” he says.

“So it is helpful to have some managers as contact officers, because in a lot of cases, other managers want to talk about these things, too. And they’ll be more comfortable talking to people at the same level. But yeah, just having your HR team and a handful of shift supervisors or managers as the contact officers defeats the whole purpose of it.”

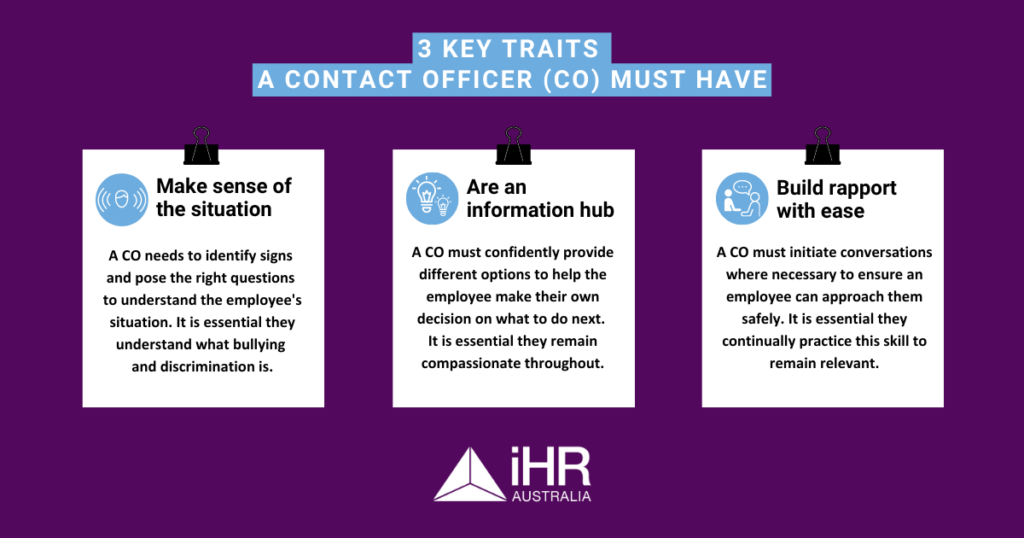

Key qualities of a Contact Officer

A contact officer should strive to establish positive, nondiscriminatory work environments by providing adequate support and being a facilitator for conflict resolution. For this purpose, in iHR’s upskilling workshops for contact officers, we help participants build confidence to gain other employee’s trust quickly through conversation. So part of this is about maintaining confidentiality so employees feel assured that a sensitive topic does not turn into office gossip.

What are some key traits of a contact officer?

Sebastian looks at some prime qualities that can turn an employee into a trusted contact officer and “the trust around confidentiality comes down to a contact officer who can be a good listener, which is not an easily acquired trait.”

“I find the people who are nominated as or if there’s an expression of interest for contact officers, it’s usually those people who are prepared to act in a way that’s consistent with their organisational values.”

“They’re good role models from the start,” he adds.

Harvey also reiterates how being discreet is a valued quality for a contact officer. And that being present and listening to an employee’s concerns in a supportive way makes a contact officer an important asset for an organisation.

Top 3 risks of stepping into the role of a Contact Officer

Here’s what Sebastian believes are the biggest risks associated with being the first point of contact in a workplace for sensitive matters:

1. Knowing whether the information that you’ve been provided triggers a ‘duty of care’

This is one of the biggest risks because there may be times when employees share information that potentially triggers a duty of care, but the employee is reluctant to do something about it.. “Quite often people will come to you (the contact officer), because they don’t want to talk to others about an issue. Although your priority is to work with the person to make them aware of their options, sometimes they won’t take up one of the options. Where the issue involves something like harm to self/harm to others or something that triggers mandatory reporting (eg. under the organisation’s code of conduct) the contact officer may be required to discharge that duty of care.”

2. Contact officers aren’t in a position to tell people what to do

The second risk is that people tend to look at contact officers as subject matter experts. And so employees will look for advice on what to do next. “And as much as a contact officer might form a view as to what would be the appropriate path to go down, contact officers can only put forth options and talk through the pros and cons of those options to the best of their abilities.

3. Being affected by people’s stories of trauma

As contact officers will be exposed to people’s stories of trauma, “we do need to talk about the self care factor,” says Harvey. Contact officers are largely burdened with those serious conversations and are constantly concerned about the people, and so, being mindful of their own mental wellbeing is also a crucial part of the role.

Where to next?

iHR Australia conducts public, in-house and virtual workshops to manage and respond to workplace issues like sexual harassment, bullying and discrimination. We also go a step further to alleviate the complaints handling processes by upskilling key people such as organisation’s leaders and employees to help drive better outcomes for a modern workplace.

Recent articles

![Lee Witherden v DP World Sydney Limited [2025] FWC 294 (2) Workplace policies](https://ihraustralia.com/wp-content/uploads/bb-plugin/cache/Lee-Witherden-v-DP-World-Sydney-Limited-2025-FWC-294-2-1024x539-landscape-dc731230e07743843bfa2c830cc42561-.png)

Smart Workplace Policies, Stronger Cultures: Compliance Made Clear