Psychosocial risks - the new emphasis on leadership to proactively identify and control them.

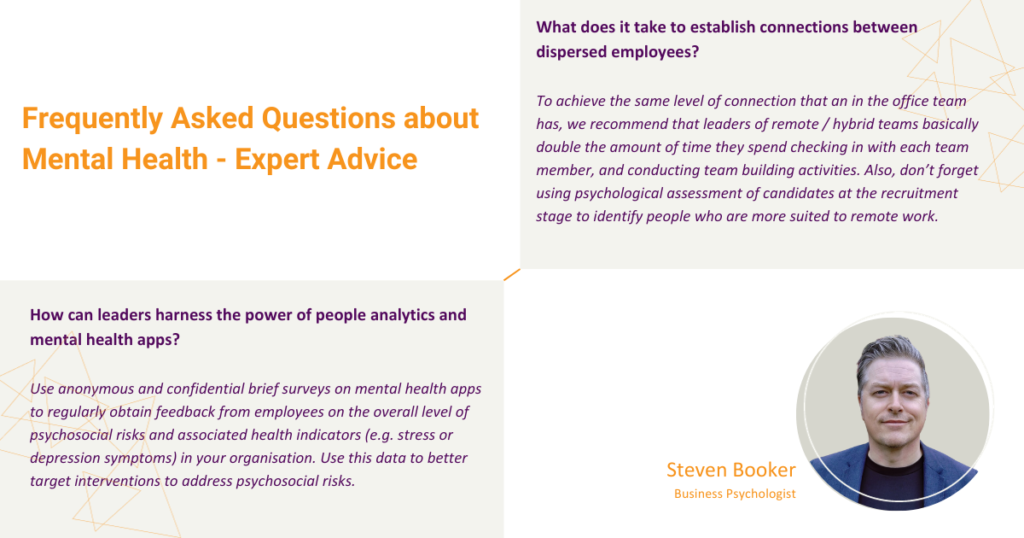

Interviewee: Steven Booker, Consulting Psychologist

When it comes to opening up about mental ill health (or reporting on psychosocial risks), many employees have a deep-seated fear of facing criticism, judgement, or discrimination. This fear often compels them to continue to suffer in silence. Justifiably, a study conducted by Diversity Council Australia (DCA)1 revealed workers who were open about their mental health were two times more likely to report experiencing discrimination and/or harassment at work compared to those who kept their struggles hidden.

But, it’s high time we kick this stigma to the curb and break the mental health taboo in workplaces.

In recent years, many leaders are becoming self-aware and upskilling themselves to better recognise the signs of mental ill-health at work and drive supportive R U OK? conversations. However, some organisations are still missing the mark.

The focus is often on identifying employees experiencing mental ill-health, assessing their fitness for work, providing them with support (if needed), and helping them build resilience. This occurs at the expense of a systems-focused approach that seeks to identify and change aspects of workplace cultures that cause stress in the first place (e.g. psychosocial risk control).

However, the new emphasis in the Australian legal system on proactively identifying and controlling psychosocial risks makes it critical for leaders to shift their thinking and focus on how to:

- Proactively identify and benchmark the level of psychosocial risks in their workplace.

- Prioritise identified risks for elimination or control.

- Develop intervention strategies for eliminating or controlling risks that are achievable given the organisation’s context, stakeholder expectations and budget.

New model WHS Regulations and Code of Practice —what it means for Leaders

Safe Work Australia’s (SWA) Model Work Health and Safety Regulations (Regulations) are not legally binding on employers unless their state or territory has implemented them in its own legal system.

For example, NSW has implemented the Regulations summarised below but Victoria has not implemented it as of yet (although the Victorian law does require employers to eliminate/control risks to psychological health).

Safe Work Australia’s (SWA) Managing Psychosocial Hazards at Work code of practice published in July 2023 (Code) is also not legally binding but provides practical guidance to employers for how to comply with their obligations to eliminate or control psychosocial risks.

In summary, the Regulations and Code require employers to, as far as is reasonably practicable, identify and eliminate/control reasonably foreseeable (psychosocial) risks to employee psychological health arising from the design or management of work, the work environment or equipment, or employee interactions/behaviours at work.

Employers (and organisations) must maintain, review and revise measures to ensure they cultivate a safe work environment

Preventing and managing psychosocial risks at work

A ‘psychosocial risk’ is anything in relation to work (factors, structure or management of work) that may harm an employee’s mental health.

Some of the examples include:

- Workload imbalance: frequently having too much work and strict deadlines

- Lack of autonomy: feeling a general lack of control over work decisions

- Inadequate support: lack of support from managers or colleagues, leading to isolation in the workplace

- Role ambiguities: unclear job description and work structure

- Poor change management: disorganised management leading to stress and anxiety

- Inadequate or unfair reward and recognition: Feeling underappreciated and unmotivated to perform

- Poor ‘organisational justice’: this could include unfair grievance handling procedures,

- Exposure to traumatic events or material: for example, inadequate support provided to employees in healthcare to manage extreme conditions

- or isolated work: Lack of resources to support and stay connected to remote staff

- Working in difficult physical environments: Challenging physical working conditions, such as, faulty machinery, poorly maintained amenities and more

- Psychological safety issues: Fear of violence, harassment, discrimination and bullying

- Workplace conflicts: stressful and hostile work environments due to persistent conflicts

When we closely examine these stress-related factors, a few notable concerns come to light.

Autonomy’s effect on employee’s mental health

According to a Journal article ‘Job autonomy and psychological well-being: A linear or a non-linear Association‘2 published on Taylor and Francis Online, the study concluded a relevance for job redesign by indicating that higher levels of job autonomy may be beneficial for the psychological well-being of workers. Although some employees have structured roles with high levels of policies or standard procedures to comply with, there is little discretion over how work needs to be completed.

Other research has also indicated that having low control at work may create stress by: restricting an employee’s ability to maximise on their full potential, reducing the coping mechanisms available to employees for managing other job-related stresses, and making it difficult for employees to anticipate challenges or changes.

Role ambiguities and overwhelming workload – a common cause for stress

Similarly, a related psychosocial risk occurs when employees don’t have clear job descriptions or KPIs/competencies/values by which their performance is assessed. This can also lead to a decreased level of control because it can make it hard for employees to know what they are expected to do, how their performance will be assessed, and how their responsibilities are separate from those of their colleagues.

Unreasonable job demands, such as excessive workloads within limited time frames, can cause stress by making employees feel that the demands of their role exceed their ability to cope. When employees perform their tasks in a fashion that involves constantly rushing or being under pressure, this can overwhelm their mental and emotional resources and activate the body’s ‘fight or flight’ (stress) response.

In an article featured on Smart Company3 in February 2023, there was a sincere appeal to organisational leadership to ‘put more thought and collaboration into job design’ to effectively decrease the risk of stress, burnout and mental ill health at work.

Toxic and dysfunctional work cultures

Toxic organisational cultures characterised by a lack of support or trust can erode employee perceptions of psychological safety, and create an environment where employees are on constant alert for threats. In turn, this can also activate the chronic stress response. The same can be said about remote work arrangements given that it often provides less scope for employees to get support, and build trusting work relationships.

Five steps to reduce the toll work takes on mental health – A Manager’s Toolkit

In recent times, there has been a significant amount of discussion both in research studies and online forums, including platforms like LinkedIn, regarding the extent to which organisations are evolving to encourage employees to ‘bring their authentic selves to work.’ This issue is particularly critical when addressing mental health challenges, as many employees, as supported by research, often grapple with conditions such as depression silently.

Just as in any change-making process, a shift in the workplace culture related to mental health awareness must begin from the top, and managers should play a more active role in this regard.

- Focus on giving employees in your team or organisation more control over how and when their work is done, and more notice of, and input to, decisions and changes that affect them.

- Be aware of the key psychosocial risks discussed above, and ensure your organisation has a structured and valid process for identifying, prioritising and controlling any of those risks in your workplace.

- Have a good, practical understanding of how stress and mental ill-health conditions may affect employees’ performance, engagement or communication at work. Check in regularly with your team, and if you see changes in an employee’s behaviour that is unusual for that person, initiate an R U OK? conversation.

- Practice authentic leadership and model the behaviour you encourage employees to exhibit. Be open about your own challenges with stress or mental health, as this will normalise discussions about this at work and encourage employees who are struggling to ask for help.

- The increased obligations to identify psychosocial risks mean that spotting and taking proactive action to address risks is an essential leadership trait, and this can only be achieved through appropriate mental health and well-being training.

But spotting and acting on psychosocial risks is not a straightforward process because they can sometimes be harder to see or understand than physical risks. Or, we may not be used to considering psychosocial risks as risks at all. For example, we may just expect that having too much work and not enough time to do it is a standard feature of a company or industry we work in.

All leaders would benefit from practical training to help them identify common changes in employees’ performance, engagement, communication or behaviour at work which may indicate high stress levels of possible mental ill-health conditions.

Resources*

-

- Job autonomy and psychological well-being: A linear or a non-linear association?, Taylor and Francis Online, 2022

-

Design better jobs: Proactive approaches to mental health in the workplace, Smart Company, 2023

Recent articles

Overcoming the Middle Manager Sandwich: CEO Strategies for Success